Both Sides Now

It’s 2026: Do you know where your newsroom is?

Starts and ends of years tend to inspire prognostications, and I’ve been as guilty as anyone. So here goes. Again. (The last time, I promise!)

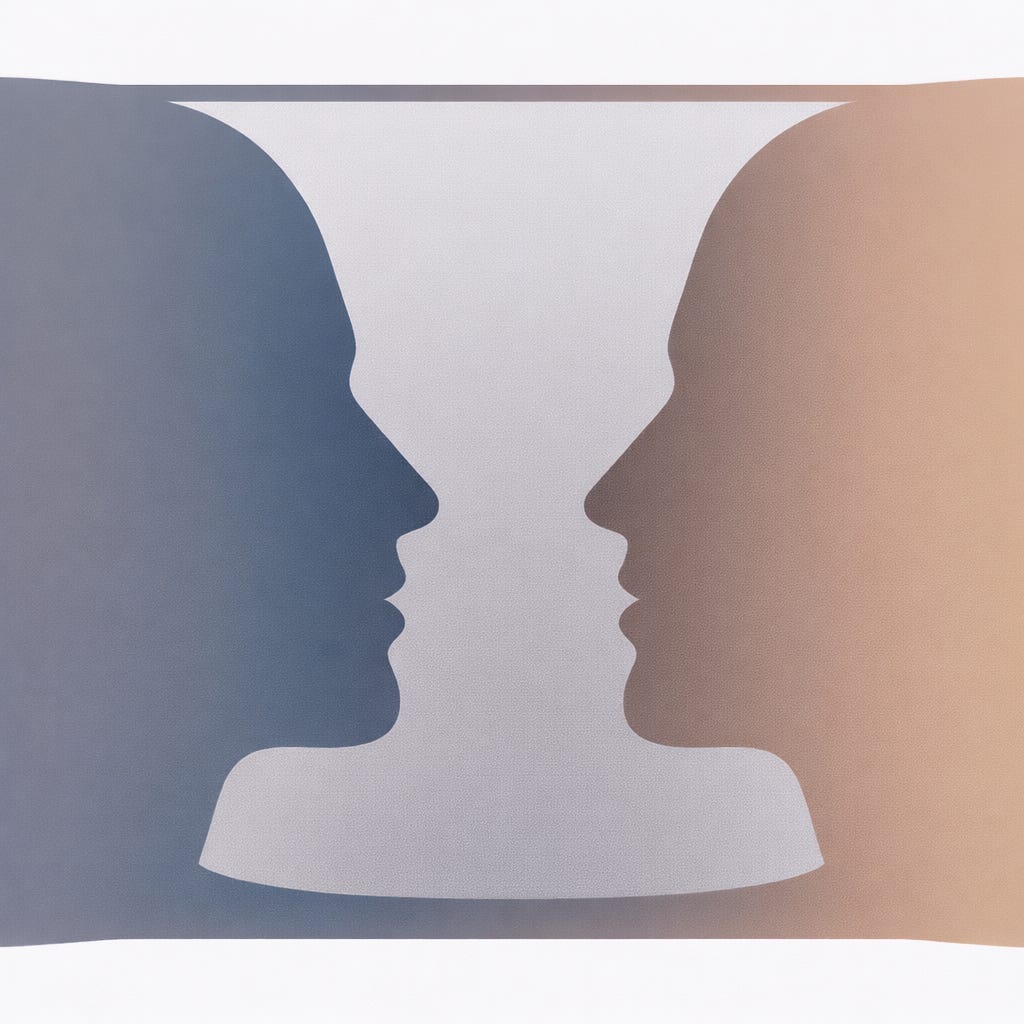

And if there’s one thing I have in mind, it’s that we need to be of two minds. More often.

Our debates about AI tend to push us to take a side: Will AI turn news into a commodity, or drive people to human-created content? Is technology a path to serving more people better, or the road to a world of slop? Should we embrace LLMs or wall ourselves off from them?

And perhaps the biggest question: Is journalism essential to our information future or are we missing the bigger picture when we obsess over our role in it?

Yes.

The future is all those things, and more, and simultaneously. That doesn’t mean all-sides-ism, or paralysis, but it means being able to understand, and even embrace, multiple contradictions if we’re to navigate a fast-changing world and meet our mission of serving the public.

Will content be king, or a commodity? And is scale the answer, or do we need to think smaller? Organizations (or people) who can offer something genuinely differentiated — whether in voice, or perspective, or fresh original reporting — and have the marketing skills to capitalize on it can likely capture a market that wants to see and hear and read what they create. For those with a compelling and unique proposition — think Taylor Swift or Joe Rogan — selling authenticity and humanity may be a path to amassing a large, lucrative following.

They will form what Tony Haile calls “archipelagos of trust”: a defensible business perch, but not a solution for the public information ecosystem — the essential, but more prosaic day-to-day news and information we need. That part of the universe is up against AI systems that can extract information and recombine it into personalized narratives at nearly no marginal cost; information creation — even quick scoops — doesn’t really deliver an enduring competitive advantage in that world. And where content is a commodity, value likely comes not from stories, but from understanding at an individual level what information people want and how they want it. And in that world, sustainability looks much more like building ties to a tight-knit audience whose needs can be superserved via AI tools.

So both propositions can be true. It just depends on what part of the ecosystem you’re worried about: Your own news organization, or the broader public sphere? If we retreat to sustainable islands of like-minded audiences, who will be building — or at least advocating for — more public-minded AI information systems?

Will personalization finally allow us to serve the communities we have historically overlooked, or push us into filter bubbles of one? So many groups have been so ill-served by the economic and technological imperatives of one-size-fits-all stories that need to go to as wide an audience as possible; nearly zero-cost personalization via AI systems finally offers an opportunity to present the same event through multiple perspectives and cater to different interests and communities. But it also risks fragmenting us into smaller and smaller filter bubbles, with fewer and fewer shared perspectives and understanding of events. The old world served too many people too badly; the new world risks serving each of us better, but all of us worse.

What systems can we build that both serve those we’ve failed to serve in the past, but also help us see how others see the world?

Is AI the solution, or a sideshow to real journalism? It’s hard — impossible — to ignore the impact of AI on audience behavior, regardless of whether it’s good or bad for the public information ecosystem; and journalism has always had to grapple with new technologies, however much journalists may have hated them at first. AI at its best offers us astounding new capabilities that we’d be foolish to ignore. On the other hand, it’s easy to be distracted by shiny objects; there’s a temptation among some — it definitely afflicts me — to try to throw AI at solving every problem, even when it’s not needed. What should matter is the mission — serving the public with the information they need. If we can accomplish that with AI, that’s great. If AI can accomplish that without us — well, that’s a more uncomfortable question.

There’s more, but you get this idea. Are chatbots still terrible at providing coherent, trustworthy answers, or are they surprisingly capable? Is AI an existential threat to public information, or a generational opportunity to improve it? Yes, yes and yes.

Some of these contradictions are really about what question we’re asking ourselves: Are we trying to solve for the public information system, for the survival of journalism, or for the survival of our own newsroom? All three are important goals — and likely need different solutions, and different ways of looking at AI. It’s helpful to be clear what we’re focusing on when we discuss AI and journalism, or we can end up just talking past each other.

And not everyone needs to try to solve everything. A small newsroom should be focused on its survival; or at least on the survival of public information to the community it serves. Better-resourced organizations may have more time to think about what lane they can best play in, and build out strategies to get there. And think tanks — and funders and investors — should be looking at the broader questions of how public information can survive, and ideally thrive, in an AI world. Even the uncomfortable ones.

Journalism, after all, isn’t the same thing as the public interest information system, any more than medicine is a synonym for the public health ecosystem. We all want better public health outcomes, and by and large medicine is part of that solution — but it isn’t the only one. And many of us wouldn’t bat an eyelid if we could get better public health with fewer doctors, nurses and less medical infrastructure. (If you don’t like that analogy, try public transportation: There are loads of people employed as drivers of cabs, buses and subways, but most of us would be perfectly happy in a world of safe, driverless vehicles.)

And so it goes with journalism. We all want a more robust public information ecosystem, and I firmly believe that we’ll need journalists and journalism to accomplish that. But we’re part of the solution to an end goal; not the end goal in and of itself.

That’s another contradiction we have to hold in our heads as we grapple with this new and changing landscape.

Now I’ll brace for the hate mail.

PS: We posted a survey about what you’re seeing in web traffic that we’d love for you to fill out. Please fill it out. Pretty please. (Amazingly, our posts are better when we have facts behind them. Not always, but usually.)

Got Facts?