WWCD?

What Would Claude (or ChatGPT) Do? (The LLMs respond to my last post.)

Every time I draft a post here, I turn to Claude to push back against the thesis; it’s a useful exercise that helps me look past some of my blind spots. Sure, it might be better to have a real human look at it too — and I do run these all past Tow-Knight Program Director Adiel Kaplan for a reality check — but it can be hard to rustle one up at midnight, when I’m hungry for feedback.

Claude’s responses are usually pretty decent — perhaps a little pat sometimes, but it’s certainly shown no hesitancy in being snarky with me, as I’ve documented. But lately — now that I have trial access to ChatGPT Pro — I’ve decided that the best way to get even more, and more developed, feedback, is for Claude and ChatGPT Pro to hash it out among themselves before they come back to me.

And that’s a fascinating exercise.

So I’m going to write two posts: One about how this process of bot-on-bot discussion has gone, and what I take away from it. And one about the actual contents of what they say.

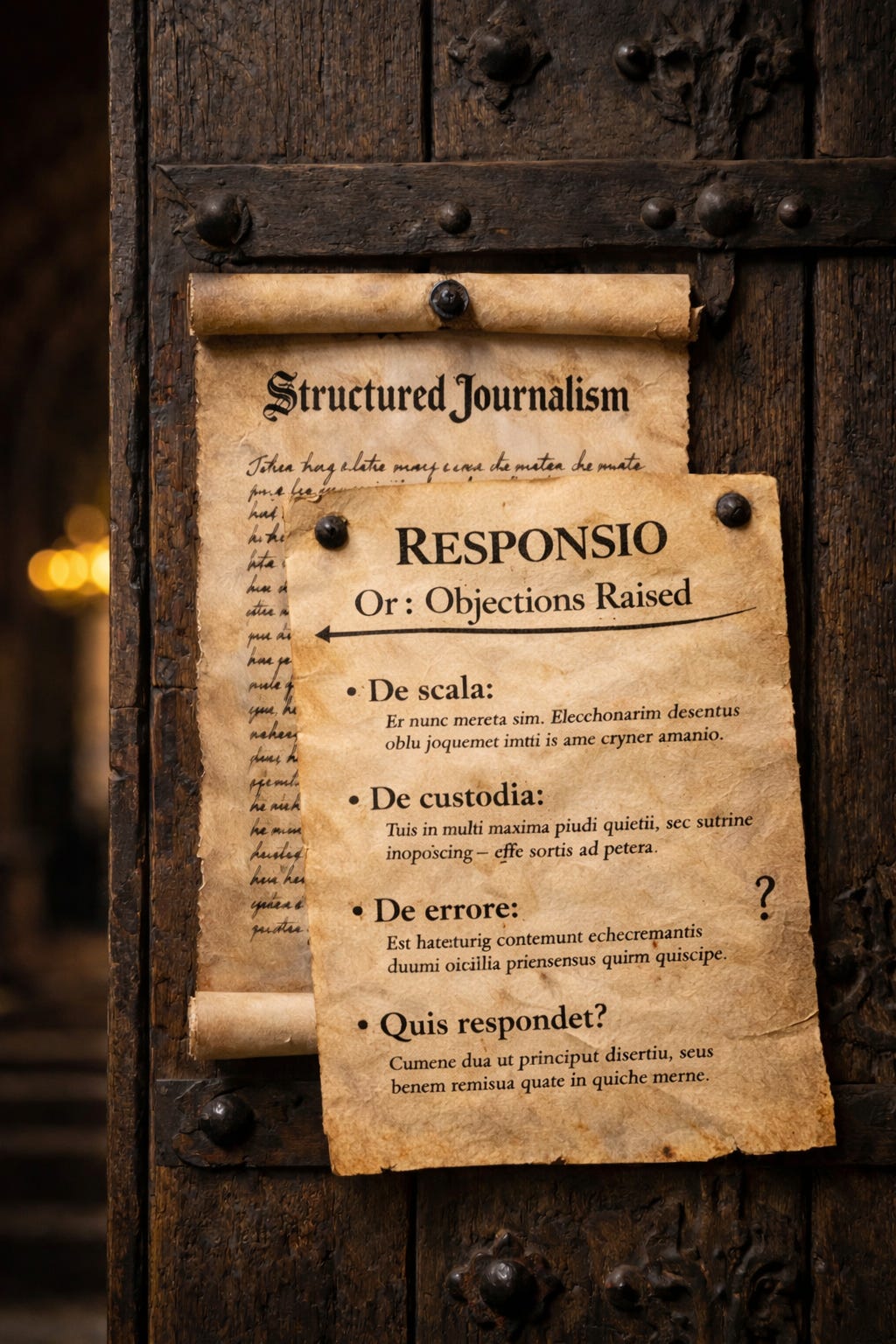

This is the second one. (The first will come a couple of weeks later.) And it’s about their critique of the manifesto on structured journalism I just posted.

If I’m going to nail something to the cathedral door, after all, I figure the church should get equal time to push back.

So here goes. (This is the end product of both of them going back and forth for a while, so there’s a paucity of snarky rejoinders from them. Also, Claude is way funnier than ChatGPT, so that would be a lopsided exchange.)

The core issues the two LLMs raised are accountability and scale, gatekeeping, and business models. Filter bubbles, too, which I addressed in the previous piece, but will come back to.

And I confess: I don’t have great answers to all of these, other than to say, we have to take them into account as we build. We already suffer from all these issues, and AI might exacerbate them, but we also have an opportunity to make things better.

Accountability and Scale. The first point is simple: If a human screws up a story, we know who to blame. (Or sue.) Who owns the mistakes in a personalized, AI-generated story? (And both LLMs called me out for comparing AI error rates with human error rates: Machines can make more mistakes and faster, even if their error rates are relatively low compared to humans; and how do we even know there’s an error, if there are 100,000 different versions of the same facts?)

It’s a really good point, and my main defense — that the world is already going to chatbots for news, even with high documented rates of hallucination, isn’t really a defense; it’s just pointing out that the world is imperfect, and we could make it slightly less bad. (I mean, that’s an improvement, but hardly satisfying as an answer.)

And so whatever system we build needs to incorporate: regular auditing of output; adversarial systems that constantly test responses for deviations from structured knowledge; and a process for quickly and transparently responding to those prompts (or complaints.) The promise can’t be “we won’t get things wrong” — because we will — but that “when we do get it wrong, we’ll move quickly and clearly to fix it and explain what happened.” That we’ll use the systems that might propagate errors at scale to also correct them at scale, and at speed. And we need to put a human in charge of that process.

Gatekeeping and Filter Bubbles. What about gatekeepers? We know who they are now: it’s the journalists and editors who run the various newsrooms we subscribe to. Who will oversee the algorithms that will decide what goes into the story I read, versus the one you read? Right now I can choose to read The Guardian instead of Fox News, or the National Review instead of the New Yorker. What happens when a machine curates facts and analysis for me?

That ties in with the issue of filter bubbles. Will I even know what I don’t know; what information I haven’t been given?

And that may be a design issue more than anything else. Can we build outputs that not only show us what matters to us, but allows us to see — even if briefly — what other perspectives might be, what key questions others asked, what facts were excluded from the story I got? I’ve prototyped these, so I know they can be built; the main question is how to compress the information they spit out.

We can obviously overdo this, of course, and end up with a 400-word story that has a 800-word appendix; but we should center the idea that we want to superserve users — and then add a little cognitive friction to their reading. It’s not a perfect solution; but a perfect solution would involve force-feeding readers both The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal editorial page, and that’s not happening, either.

Business models. How will we make money on personalized news? For me, it’s an article of faith that if we can superserve our readers with information that’s useful and relevant to them, we can build a loyal community — and that that opens up potential paths for revenue streams: subscriptions, targeted advertising, in–person events, philanthropy. Knowing your audience — customers — well has historically allowed us to bring in revenue, whether directly or through marketing access to them. But I concede it’s as much an article of faith as it is any kind of deeply thought-out strategy.

None of these answers are truly satisfying, and I certainly don’t have certainty they can be solved.

But I do have certainty that our existing issues also don’t have satisfying answers, and that we can at least map some possible solutions in this space, not least because we’re still in the early stages of inventing this new ecosystem.

Mostly I’m certain that the three-way conversation I had with Claude and ChatGPT pushed me harder to think about the ideas I was mulling. It certainly pushed Claude to praise ChatGPT, which I’d never seen it do before.

ChatGPT is right on almost everything—and identifies the gap I missed.

…

So: credit where due.

And then it decided to nudge me. Because.

Ship the manifesto. Write the follow-up. Build a tool. Stop letting us talk about ourselves.

Thanks, mom.

Good. Hugely interesting.